OPINION: What is new in this latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report is the clarity of the messages: climate change is real; we’re responsible; it’s here now; things will get much worse unless we take drastic action. (There is also a nifty interactive atlas to explore climate changes in different regions over time).

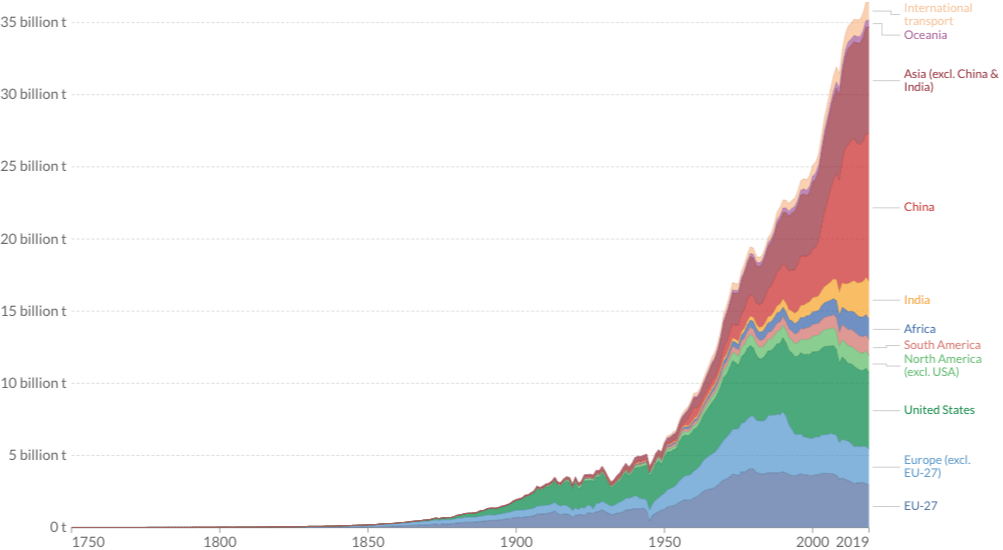

Table SPM.2 in the Summary for Policymakers indicates that if we want to increase our chances of not surpassing the 1.5 degree increase over preindustrial levels to at least 83 percent, we must limit our global carbon budget to no more than 300 gigatonnes of CO2. That’s all the fossil fuel we get to spend globally. This is seven and a half years of the approximately 40 gigatonnes per year we used up until 2020.

Even the 1.5 degree target has multiple harms outlined in the report that we will not be able to avoid. But every little bit of increase over 1.5 degrees will make things worse, and if they are much worse, we may be on a slippery slope to perdition.

If world governments were to take this 300 gigatonne emission target seriously it would mean a dramatic decline in fossil fuel use. This would require something like an annual reduction of fossil fuels to only 10 gigatonnes per year for the next 30 years, or just 20 percent of what we now use. Non carbon greenhouse gas emissions will also have to decline rapidly.

Actual emissions reduction clearly needs to play the major role in moving forward. The report clarifies that with increasing global heating, the capacity of oceans and land to absorb greenhouse gases is declining, meaning sequestration will have less of an impact. This doesn’t mean we should stop planting trees, but that we should plant even more.

The big dilemma these scenarios create for us is that we do not have alternatives to fossil fuels readily available to take their place. Yes, solar panels and wind turbines can provide electricity, and in many cases less expensively than fossil fuels. But building up the capacity of wind and solar, and other so called renewables, to replace fossil fuels brings us face to face with yet another dilemma. We need fossil fuels to build solar panels and wind turbines. This would mean an increase in fossil fuel use at the very moment when we have to dramatically reduce their use.

And we have been deluding ourselves about these technologies being “renewable.” They are not. Yes, the sun shines and the wind blows, but to capture these natural processes and turn them into electricity requires an industrial society with mining and heavy industries to provide the raw materials to build, transport, install and maintain these technologies. All these activities rely on fossil fuels.

All the raw materials required for these technologies are non-renewable. This means these technologies would only be useful for a few decades even if we had time to scale them up to replace fossil fuels. Some of the rarer minerals required are not available in sufficient quantities to rebuild the global energy infrastructure to replace fossil fuels.

Some materials can be recycled and recycling will undoubtedly play a role in our future. But recycling materials takes energy and that is the resource which will become increasingly scarce. Seems like our dilemmas are compounding rapidly. And there are more.

Reducing fossil use means constraining GDP

Economic activity is strongly related to the amount of surplus energy available in society. This has been the gift of fossil fuels – large pools of surplus energy to build our complex industrial civilisation. But we now have to stop using fossil fuels to ensure a safe climate. The implications for our economies are staggering.

Reduce energy use by 80 percent (to succeed with an 83 percent likelihood of having a safe climate) and you inevitably reduce economic activity as we know it. The basic paradigm of our civilisation comes into question.

The latest IPCC report does not comment on the relation between the need to rapidly move away from fossil fuels and the implication for economic activity, but there is clear evidence that reducing fossil fuel use will require a major rethink of the goal of ever increasing GDP.

Fortunately, there have been a number of fringe movements in both the professional and activist communities who have foreseen these dilemmas. They have been developing proposals for dealing with the new realities that have been highlighted by the latest report, and other relevant research.

Some traditionally-trained economists have recognised the inherent flaws of our current neoliberal economic model and developed new conceptual approaches to economic theory. Most prominent are ecological economists who reformulate and integrate economic theory with basic biophysical laws of thermodynamics.

That is just a fancy way of saying that this approach understands that economic activity is a subset of the environment, and that there are biophysical limits to continuous economic growth. But the end of growth need not be the end of prosperity, as articulated by British economist Tim Jackson. It depends, of course, on how we define prosperity – strictly in materialistic terms, or in terms of human wellbeing.

A Canadian ecological economist has shown that it is possible to operate a complex society such as Canada’s, without growth, and still maintain employment, contain inflation, manage debt, and reduce inequality. The Doughnut Economics movement is based on ecological economic principles and makes the issues of dealing with limits and emphasising human wellbeing accessible to everyone.

The new economic perspectives are much more than just broad ideas of what a new economic model might look like. College textbooks have been written and translated into multiple languages, and there are examples of many of the proposed policies actually being trialled in different jurisdictions.

Respecting the planet’s limits

What are some of the options that would be needed for an economic model that doesn’t destroy the environment but provide for everyone’s needs? Here are just a few examples that come to mind specifically in light of the inescapable changes outlined in the IPCC AR6 Report. Interestingly, many of these examples designed for economic transformation are also what is needed for adapting to the inevitable climate impacts we cannot avoid.

The most basic rethink we need is to recognise that biophysical limits are a reality that any economic system must respect. If we accept that the purpose of an economy is to provide goods and services for each other (rather than to generate profit and become wealthy), then we have a very different focus to economic decisions. Human wellbeing, having the goods and services we need and wish for (the latter to the extent possible within biophysical limits), becomes the goal of economic activity.

This reframing is important because with less surplus energy available the economy will inevitably circulate less material resources. Reduction in material use is not only inevitable, but also highly desirable.

Globally we are currently consuming some 100 billion tonnes of raw materials annually, most of which is non-renewable. This is a major cause of our disruption of the natural world and the biodiversity losses which are an existential threat to our survival.

Material consumption is obviously important to ensure our basic physical needs are met. But humanity’s consumption, and waste production, goes way beyond meeting our basic needs.

Beyond a relatively low level of consumption, compared to our current levels, more consumption of stuff does not lead to greater happiness or wellbeing. The evidence is clear on this in cultures around the world.

This means we do not have to be afraid of a reduction in economic growth. With less energy available, economic activity can decline and we can still lead healthy and fulfilling lives – provided we do it right.

Our current economic system treats lack of growth as a serious problem, associated with unemployment, bankruptcies, foreclosures, and considerable social disruptions. But it need not be that way.

An economy focused on human wellbeing can ensure meaningful jobs, quality education and health care, healthy low energy housing, and strong social cohesion, the basis of any successful society. It’s a matter of planning for these goals rather than simply accepting a declining GDP. Policy matters, and alternatives are available.

What are some of the practical changes that would allow for reduction in GDP without the negative consequences we associate with such a change? Along with a few other countries, New Zealand has established a wellbeing framework to assess how well we are doing as a nation. Focusing more on these wellbeing goals, rather than GDP growth, would be a good place to start.

A general consideration is to recognise that technologies are going to provide limited assistance in this transformation to a fossil free world. Yes, we should continue researching what technologies will best support the new goals we set. But we need to give up on the notion that the market is the best means of selecting which technologies should flourish. That’s what we did with fossil fuels and it’s been the biggest market failure in history.

Learning to live well with less energy is a major priority. Think negawatts instead of megawatts.

A return to manual labour

Another general consideration is that human, and some animal, labour will have to replace fossil fuels in a great many economic endeavours.

We need better housing. Many nations have public housing programs that provide well-constructed, healthy dwellings that citizens enjoy all their lives. We have to get creative about how we can learn from other countries and meet peoples’ need for secure, low energy housing throughout the country.

Food security in New Zealand leaves a lot to be desired for a large number of families. Solutions are within reach, and more supermarkets is not one of them.

The IPCC report indicates we will experience more frequent and more severe disasters. Strengthening our Civil Defence systems will become increasingly important, providing important jobs in communities across the country.

Our agricultural system is energy intensive. Restructuring our farms to make greater use of human and animal labour is one way of dealing with the reductions needed in fossil fuels. In many cases this may mean people moving back to rural areas, strengthening those communities with more jobs and money circulating locally. Local food resilience becomes an important goal.

The need for more carbon sequestration in our forests means more plant propagation and planting. We also need to regenerate natural systems we have degraded. Again, more meaningful jobs.

We need to restructure our urban areas to align with the 20 minute city concept, to make it easy and attractive for people to live, work and play with active transport options.

Expanding our health care system to ensure we are prepared for the unexpected will become increasingly important as a result of the already built in impacts of climate change. We will have more disasters to deal with, as well as more pandemics.

Small and nimble

These are only a few of the many ways we can change our economy to align with the new realities the IPCC report highlights, and their implications. Economists will need to change the way they think about economic activity, but they have the knowledge to develop new economic mechanisms to support new policy priorities.

It will be difficult for governments to change their mind-sets that economic growth is the best route to prosperity. But the realities of resource and energy limits will force them to rethink priorities and goals. We need to move beyond politicians who are simply good managers and look for those with a new vision for the new realities that we face.

With New Zealand embracing a wellbeing framework, and the plethora of natural resources we have, along with good ole’ Kiwi ingenuity, we should be able to provide a model for the world to follow.

Our small size makes it easier for us to change our economic structure and show others how it can be done. Since inflation will not be a risk, the application of Modern Monetary Theory may help with the macroeconomic adjustments required.

But any government will need massive public support for these changes, as the changes jar with the way most of us have viewed the good life for many decades. Fortunately, a variety of activist groups, as well as some of the fringe professionals, have outlined community based actions that would facilitate and reinforce an economic transformation based on alternatives to growth.

By engaging in and supporting such local community building initiatives we can accomplish two important goals – we can help prepare our own communities for both adaptation to climate change and the new economic realities, as well as demonstrate to the politicians that we are ready to embrace a new vision based on biophysical realities.