Don’t be fooled by the talk of a big new tax hike. Jacinda Ardern and Grant Robertson have just put their small ‘c’ conservatism on display in their biggest election policy decision so far — to not tax wealth for at least three years, and for at least one of their political lifetimes.

Labour is painting its re-introduction of a 39c top tax rate for those earning over $180,000 as a way for the rich to do their bit in the Covid-19 recovery.

But the real news is it has decided on three more years without taxing wealth and seriously addressing both the widening inequality and stagnant productivity that has trapped a quarter of the population in poverty. Jacinda Ardern ruled out a capital gains tax in her political lifetime last year and ruled it out again yesterday. Grant Robertson, a possible successor, didn’t go quite that far when asked to rule out capital or wealth taxes in his political lifetime, but reiterated this was it on the tax front.

“What is needed right now is certainty and stability. For 98 percent of New Zealanders, there is no change in this policy, and that’s important to me,” Robertson said in answering questions about why there was no capital gains or wealth tax.

“It is really important for us to have done something here that we think is about all New Zealanders pitching in, but is about providing that level of stability and certainty.”

Ardern was similarly soothing about retaining the status quo and not scaring the horses around tax five weeks out from an election.

“This is a really difficult time in New Zealand’s history, in the globe’s history. We’ve chosen a policy that we feel balances the certainty and confidence people need right now,” she said on the campaign trail in the Bay of Plenty.

Reserve Bank figures show households that own property and have money in stocks and term deposits made over $250 billion of tax-free capital gains in Labour’s first term.

But is everyone pitching in? And has inequality gone away?

It’s the dirty little secret of the first term of this Labour-led Government. It has been fantastically enriching for the oldest and richest in the electorate, while the young, the old and poor who voted for Labour and the Greens became poorer and are even further away from affordable housing and decent incomes than they were in 2017 when they swept Jacinda Ardern to power.

Reserve Bank figures show households that own property and have money in stocks and term deposits made over $250 billion of tax-free capital gains in Labour’s first term. Taxing that would have paid for its Covid-fighting fund of $50b. Yet Labour has again reneged on its inequality-fighting rhetoric and will allow another three years without taxing the next $250b of fresh capital gains that are likely to be created because the Government has tacitly allowed the Reserve Bank to print over $100b to pump up asset values even higher.

It’s enough to spark a mass exodus of equity-rich home owners to scoop up any remaining homes as rental properties, or just to sit on the empty house and earn more money tax-free from it than from their real jobs. It’s already happening. Real estate agents report a surge of property owners through their open homes to jump on the surest of things: leveraged and tax-free capital gains from a market effectively guaranteed by the Government and too big to fail. Banks are struggling to cope with the mortgage applications, leaving existing property owners with the ability to withdraw equity from other properties in the box seat in auctions.

Yet again, older property owners have won the battle that happens at the heart at our political economy every three years over whether and how to tax wealth and capital gains to try to reduce wealth inequality. Politicians understand that more than half a million young and poor New Zealanders don’t vote and that the median voter they need to target is a home owner in the suburbs of the big cities and in provincial towns.

In 2017 those voters had to wait until just three days before the election to find out they had fended off a capital gains tax. That was the day — almost three years ago to the day — that then-Opposition Leader Jacinda Ardern announced she had dropped Labour’s policy of considering a capital gains tax in its first term, and instead only promised a review into whether to introduce one after 2021. She then never spoke up for it again over the next three years and declared it dead on her watch last year.

Even the tax experts are saying there is still a problem to solve, and that it will get worse over the next three years.

PwC partner Geof Nightingale, who was on both the 2010 and 2018 Tax Working Groups, said Labour’s tax plan wouldn’t hit the rich where it hurt.

“There’s a whole class of income that’s not currently being taxed, that’s still not going to be taxed – that’s capital gains,” Nightingale told Newshub.

“Under a future Labour government, the rich will still get richer,” he said.

Incentives to go even harder into property

It’s not just a matter of leaving capital gains untaxed. The changes proposed by Labour to add the top tax rate and to leave the trust rate at 33 percent will actually accelerate the shift into untaxed capital gains from property, and the shifting of income from work to tax-free assets.

One reason the previous National Government gave for removing the 39 cent top tax rate was to reduce the tax incentives for people to shift assets into trusts, which are taxed at 33 percent. The bigger the gap, the bigger the incentive.

Westpac Economist Dominick Stephens published a paper in 2007 showing the increase in the top tax rate to 39 cents in April 2000 increased house prices by 17 percent as property investors factored in the higher prices they could bid by moving any rental income from property into a lower tax bracket through a trust.

There are up to 500,000 trusts in New Zealand, with 325,000 or about 14 percent of all properties included in a trust. New Zealand’s trust ownership rate per person is twice as high as Australia and 16 times as high as Britain (corrected from earlier version which said Australia)

Their popularity had been waning since the 2010/11 equalisation of the top tax rates and crackdowns by MSD and IRD on using trusts to hide assets, particularly to avoid nursing home fees linked to the means testing of assets. Robertson said IRD would be given extra money to police the use of trusts, but the Law Commission wrote in 2012 about how the misalignment of the rates incentivised avoidance, reinforcing the evidence put before the 2010 Tax Working Group.

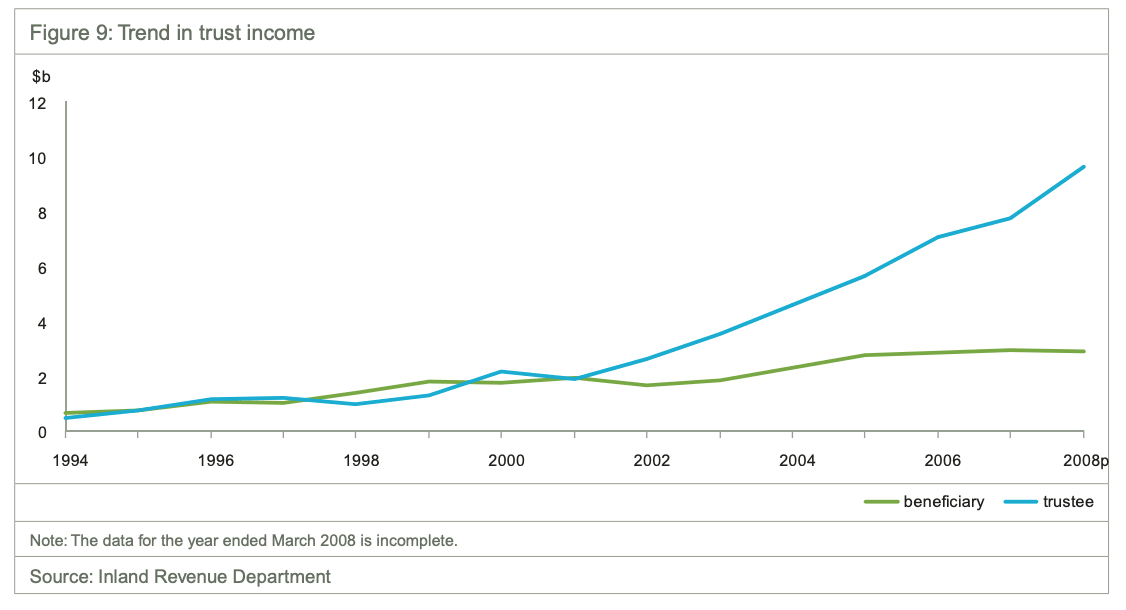

“Individuals have been able to escape higher marginal and effective marginal tax rates by diverting income to lower-taxed companies or trusts. Prior to 1 October 2010 trusts had been used to shelter income by having it taxed as trustee income (at a rate of 33 percent) rather than having it distributed to beneficiaries and taxed as their income,” the Commission wrote in a 2012 issues paper.

“This policy appears to have provided a further incentive for people to establish trusts in recent years,” it said, pointing to the chart below.

“The 2010 Tax Working Group suggests that this could indicate that trusts have been used to enable people to minimise their tax liability. It is likely that the tax changes from 1 October 2010 will reduce the incentive for people to settle their assets on trusts.”

Labour is about to make it easier for the richest, made $250b richer over the last three years, to help shelter their incomes at lower tax rates and move even harder into property.