A journalism colleague once introduced me to the concept of the “F*** me Doris” story. It was apparently coined by a former editor of the UK tabloid newspaper The Sun, Kelvin MacKenzie, and refers to a story so extraordinary or unexpected that it leads a reader to use that expletive to his wife over the breakfast table.

I use it sometimes when I get a story pitch from a public relations person. All very interesting, I say, but what hits your “F*** me Doris” journalistic radar?

I often get a ‘lol’ or a ‘haha’ in response. But the other day I got this from Jonathan Tudor, co-founder of PR agency Storicom.

“There’s a guy who has a “f*** me Doris” drone, with a Māori-Dutch name, who is using AI [artificial intelligence] and some hardware to save the Māui dolphin. The plot involves cat shit, a man called Danu Abeysuriya and fish nets (not stockings). Is this good enough?”

Any possible good news about the world’s most endangered dolphin – a mammal considerably more threatened than the kiwi, is surely good enough. But when it involves drones, AI and cat shit…

Tragedy and hope

So, I meet up with Tane van der Boon and Danushka Abeysuriya, and their project does indeed involve all the elements Tudor mentioned: a drone with super grunty (but reasonably cheap) processing capacity; a clever, though surprisingly tedious process for teaching a computer to recognise a dolphin in a sea of, well, water; and the potential to use the information gleaned from the intelligent drone to chart where the last 50 or so Māui dolphins hang out, and help keep them safe.

If we know where they go, the argument is, we can possibly save this critically endangered species from its greatest threats: fishing nets and a disease called toxoplasmosis, brought on when cat poo gets into waterways.

Dolphin project under threat

The Maui63 story starts in around 2018 with a problem. A project run by University of Auckland marine scientist Rochelle Constantine to track, count and hopefully save the (then) approximately 63 remaining adult Māui dolphins had run into difficulties.

The aircraft Constantine used to use to do an annual survey had been sold to Australia. Anyway, plane surveys are expensive and if you only do them once a year you don’t get information about where the dolphins hang out the rest of the year – which might not be the same place at all.

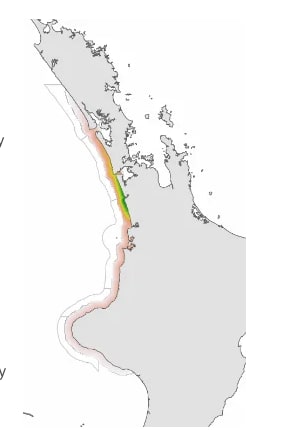

Doing the counting by boat isn’t ideal either. Hiring a boat and crew costs a lot and finding and following (or worse, 50) dolphins in the huge area of sea off the west coast of the North Island where the dolphins live, is challenging – even when the seas are calm enough to take a boat out.

Which very often they aren’t. So because scientists don’t get out with the dolphins very often, there is very little information about where they go.

And if you don’t know where they are, it’s hard to keep fishing boats and toxins away.

Enter Willy Wang, a registered doctor completing a PhD in medical science at the University of Auckland. More importantly for the project, Wang is also a drone enthusiast and looking for commercial applications. He and Constantine started talking about using drones with cameras to find and count dolphins.

Drones can cover big areas, go out in more gnarly weather than planes or boats, and are way cheaper to operate than manned craft, so the pair reckon they could gather more data, more often using drones.

But that brings up other problems: like how scientists could possibly trawl through what could be thousands of hours of drone footage. And even if they had the time, how they could spot the dolphins in all that sea.

Which is where van der Boon and Abeysuriya come in. The former is an IT guy working in the steel industry and pondering the options of using cameras and artificial intelligence in safety systems.

But van der Boon also had a lifelong passion for conservation – “My parents were old hippies; I had a classic West Auckland upbringing.” And when he heard about the dolphin project he wanted to get on board, joining with Constantine and Wang to form the not-for-profit MAUI63 – with the mission of “saving the world’s rarest dolphin with technology”.

(As well as being the name of the dolphin, MAUI also stands for “marine animal unmanned identification”).

The MAUI63 drone can fly for six hours at a time at 140-160 kph. Put that into the sky every couple of weeks and that’s a lot of footage.

Van der Boon developed a rough prototype of an intelligent drone camera system which could collect all the video footage and process it in real time to recognise dolphins, record where they are and follow them.

It sounds easy. It isn’t.

Teaching a computer

What MAUI63 is doing is cutting edge internationally in the field of artificial intelligence known as ‘computer vision’.

It’s all about using deep learning models (and a lot of boring legwork) to train computers to take digital images from cameras and videos, identify and classify objects — and then react to what they “see.”

Humans do this really well, even young ones. Any three-year-old child can see a dog, process that information, and know it’s a dog. They can likely do the same with all manner of things, including dolphins.

Computers, on the other hand, are pretty hopeless at being able to interpret what they “see”.

“I spent hundreds of hours drawing boxes around dolphins on screen for the AI. Dolphin, dolphin, dolphin, not dolphin. I got pretty sick of that.”

Take the example of a dog. To teach a computer to recognise a dog, you need to show it loads and loads of digital images of dogs and let it build up a memory of what a dog is – and what it isn’t. German shepherd – dog, chihuahua – dog, mastiff – dog. But a cat – which has lots of similar characteristics – that’s not a dog. A possum – not a dog. Terrier – dog, child in a furry suit – not a dog. Black lab – dog, golden lab, also dog. Small version of the above – yup, dog.

Van der Boot says although he’s passionate about the MAUI63 project, teaching the computer to recognise a Māui dolphin wasn’t much fun.

“It’s not glamorous. I spent hundreds of hours drawing boxes around dolphins on screen for the AI. Dolphin, dolphin, dolphin, not dolphin. I got pretty sick of that. It’s like being a diligent parent teaching a child.

“You need to give it a lot of data.”

Still, after a while – and given intelligent software and enough hours spent showing a computer images and telling it “dog” or “not dog”, dolphin or not dolphin, an intelligent system will start to build up its own ideas, so that if it sees something in an image or a video which fits (or doesn’t fit) the parameters, it will be able to have a pretty good stab at guessing if there’s a dog or a dolphin in the shot or not.

The MAUI system can pick a Māui dolphin from a common dolphin, and should eventually be able to identify individual animals. It can also switch to ‘follow’ mode when it finds one, telling the drone to circle around the area to keep the dolphin in view.

Flight tests, the first prototype, and integration of the AI with the drone was finished last year; now the project is in the process of getting Civil Aviation permits, training drone pilots and buying a fancy new drone.

Data collection and a “continuous monitoring plan”, with a drone flight every 2-4 weeks should start in January.

Once the project has built up, van der Boon wants to make all the information freely available to anyone who wants it – scientists, government agencies, fishing companies, or conservationists.

Which is where Danushka Abeysuriya comes in. Rush is providing cash and expertise for the project, including a “visualisation platform” so people who want to understand what’s happening to dolphins can see the data easily.

The guy who dodged two civil wars

I know Abeysuriya from way back – and he’s one of the more talented, creative and interesting people I’ve ever met. By the time he was nine, he and his family had experienced nick-of-time escapes from not one, but two, war zones – Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe. (For more history, check out this story by Elly Strang.)

By the time Abeysuriya was 24, he had his own game development company, Rush Digital.

Ten years later, Rush Digital has moved beyond games – it’s now the design and technology development company behind apps like the CovidTracer, the Aroha teen mental health chatbot, Z Energy’s Fastlane and the Uber & Cheers ‘Sober self chatbot”.

Rush Digital’s mantra is to “design and build technology to better serve humankind.”

Rush Digital came on board as a partner with the MAUI63 project to help with analysis and display of the dolphin drone data.

But once computers start being able to “see”, there are huge possibilities for commercialising the technology, and Rush Digital wants to be part of that.

For example, you could use it on fishing boats to check for illegal dumping, without someone having to go through thousands of hours of footage, Abeysuriya says. The computer would do the basic sifting, leaving humans to go through just a small percentage of the footage – “empty deck, empty deck, empty deck, people doing normal fishing stuff, people walking about.. Oh, not sure about what that guy is doing – I think you should check this bit of footage.”

As Abeysuriya puts it, “you use the computer to do the sniff test and leave the judgment call to humans”.

Computer vision could also be used in a factory or on a building site to check people are wearing masks or the right safety gear (“Human with hard hat and high vis vest, human with hard hat and high vis, human without…”) or to make sure there aren’t unauthorised people around (“person I know, person I know, person I don’t know”).

You could use it to identify shoplifters – the AI would be able to tell the difference between someone putting goods in a trolley or in a pocket or handbag, for example, and alert a security guard.

You could use it with robots to pick kiwifruit – in fact clever companies have been trying to do this for a while, but haven’t yet got it working right – kiwifruit are difficult.

Or you could use the technology to crunch data from security cameras in a shop to look at how customers move around the store and try to maximise purchasing.

“I could improve the performance of my business using video analytics – where in my space do I see most foot traffic. Or I could look at stock depletion. An intelligent computer system could monitor 100 cameras, notice when an item is out and tell staff.

“It’s making humans more efficient – surfacing insight and leaving it to humans to work out.”

Abeysuriya says what MAUI63 and Rush Digital are doing is game-changing.

“Technology is shifting and projects like this which improving drone technology are world leading. No one has got computer vision to this point – where you can take 35 frames a second on a device in a drone.”

Computer vision isn’t new, what’s changed is the speed and most importantly, the cost, Abeysuriya says. Being able to take a drone off the shelf, or use an existing security camera, add cloud processing power and do clever stuff quickly and cheaply.

“There’s been a lot of theory about computer vision, since MIT in the 1960s. But we are at a point now when we can commercialise it, because cost is not the main inhibiting factor.”

Take the technology to operate the camera network for a possible Auckland central city congestion charge. Media reports have suggested the system could cost $46 million to set up and $10 million a year to run.

Abeysuriya muses this could be significantly cheaper by the suggested start date.

“I reckon we could operate it for $1 million a year by 2024. The cameras won’t cost much; you could probably buy the technology from Noel Leeming by then.”

Or imagine using computer vision to patrol an area where an endangered species – dotterels or kiwis were nesting, for example. If the AI identified a dog or other pest in security camera video, it could alert someone to come and catch the animal before it killed a chick.

Night vision cameras mean you could guard the beach when it was dark too.

But the hardware has to be cheap. No one’s going to put thousands of dollars-worth of AI gear on a pole in a public place.

MAUI63 is already in discussion with other conservation groups about using the system, including to stop illegal fishing in Nuie.

Of course whether saves the Māui Dolphin is uncertain.The project is only just getting going, dolphin numbers are still falling, and even with the information gained, fishing nets and cat poo may still kill the remaining mammals. That’s largely out of MAUI63’s hands.

But van der Boon is optimistic. MAUI63 is working with fishing companies Sanford and Moana and will integrate the data the drone produces – both real time and predictive modelling – with their boats.

“Above and beyond New Zealand regulations, if we tell them we think or there are dolphins in this area, they will completely avoid them with all of their boats. That’s pretty cool.”

Abeysuriya says technology can work for good as well as the opposite. Speaking at this year’s AI show he said people wielding technology have created a lot of the world’s challenges, particularly around environmental pollution.

“But just because that’s the way it is, doesn’t mean that’s the way it has to be, and we can use technology to solve these problems.

“Never get disheartened. In 10 years we will be able to look back and say ‘We saved the Māui dolphin’.”

Or at least we tried.