Analysis: The Government’s consultation document on a climate plan falls short of its own target by more than two million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions.

Released for consultation on Wednesday morning, the draft Emissions Reduction Plan is more like half a plan and half a plea for new ideas to reduce emissions. The Government has accepted the emissions budgets proposed by the Climate Change Commission in principle, with slight adjustments to account for new data about projected emissions from the forestry sector.

Under the first of those budgets, which covers 2022 to 2025, New Zealand’s emissions would be limited to 292 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2e) – about 7.7 Mt below the projected levels over the next four years under current policies.

The new policies in the plan which have had their emissions impacts calculated are expected to contribute reductions of between 2.6 and 5.6 Mt CO2e, leaving a gap of at least 2.1 Mt. That gap could be filled by proposals within the plan that have yet to be evaluated, by new policies that result from the consultation or by effort from the private sector.

“Government policy will be crucial, but so too are the plans and strategies you will develop to reduce emissions in your own organisations and communities,” Climate Change Minister James Shaw wrote in the introduction to the draft document.

On Wednesday, he told reporters that it was “not a draft of the emissions reduction plan itself, rather it is an opportunity for people to feedback on what should be included in the plan”.

He said the lack of a focus on agriculture in the plan was because any results from the Government’s work programme with the primary sector will be consulted on separately.

“We didn’t want to waste people’s time by including things that have either already been consulted on or have other kind of engagement processes elsewhere.”

Parts of the plan set out specific policy proposals, like making it easier for councils to convert road space to walking and cycling corridors. Others merely raise potential policies and ask for feedback. Some of the Climate Change Commission’s most controversial recommendations, like a 2025 ban on new gas infrastructure in buildings or a ban on the import of fossil fuel vehicles by 2035, fell into the latter category, with the Government not taking a specific position on whether they should be implemented.

Transport the main focus

Overall, the plan expects emissions reductions from energy and industry to make the largest difference in the next four years, with the transport sector coming in second. The bulk of the document focuses on transport, however, because policies in that area need to be set many years before their full effects begin to be felt.

As part of the effort to reduce transport emissions, the plan sets four targets for 2035. These include reducing the distance travelled by cars and light vehicles by 20 percent, increasing zero-emissions vehicles to 30 percent of the light fleet, reducing emissions from freight transport by a quarter and reducing the emissions intensity of fuels by 15 percent.

Most of these are in line with the commission's own pathway out to 2035, although the Government takes a more pessimistic view on electric vehicle uptake in the next 15 years. The key difference comes in trying to make up for that discrepancy - the Government's focus on reducing vehicle kilometres travelled by a fifth contrasts with the commission's expectation that distance travelled increases by 23 percent by 2035.

In order to achieve more ambitious rates of walking and cycling, the Government will review transport plans in Auckland, Tauranga, Hamilton, Wellington, Christchurch and Queenstown to ensure they're aligned with the 20 percent reduction target. If they aren't, then the plans could be revised to focus on high-density development along public transport corridors and reallocate "significant amounts of road/street space to rapidly deliver more dedicated bus lanes and safe separated bike/scooter lanes".

Planning laws and regulations could be changed to "streamline" the requirements around consulting the public and "to make it easier for local government to reallocate road/street space ... and create an expectation that this will occur".

New highways and road expansions will also be reviewed to make sure they "are consistent with climate change targets and avoid inducing further travel by private motorised vehicles".

Alongside reducing the reliance on cars, the transport components of the plan focus on "adopting low-emissions vehicles and fuels" and "decarbonising heavy transport and freight". This latter objective would be primarily achieved through the use of biofuels in trucks and through shifting freight to lower-emissions alternatives like rail and coastal shipping. The plan also proposes requiring all new small-passenger, coastal shipping and recreational ships to be zero emissions by 2035.

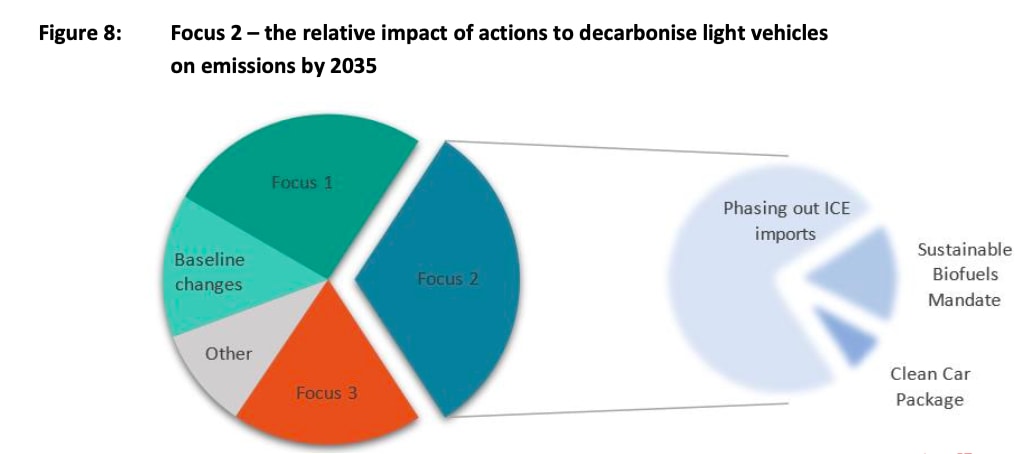

Although the plan doesn't take a position on a potential ban on fossil fuel vehicle imports, this policy (or something similar) is needed to make up three-quarters of the emissions reductions from the "adopting low-emission vehicles and fuels" goal, which in turn contributes to just under a third of the overall emissions reductions from transport by 2035.

Little focus on agriculture

Proposals in other sectors were less specific than in transport. The Government is considering the commission's recommendation to set a renewable energy target, but hasn't taken a position on the issue. In the buildings sector, the plan moots capping emissions from operating buildings and emissions from fuels used to operate buildings. It also floats financial incentives for lower emissions buildings.

In waste, which is responsible for 4 percent of the country's gross emissions, more robust measures to capture methane from decomposing food were proposed. Landfills that receive organic waste will be required to have a gas capture system by 2027, which can then use that gas for energy or convert it to less harmful carbon dioxide. Landfills without the ability to install such systems won't be able to receive organic waste.

The plan also entertains banning food, and green and paper waste from ending up in any landfills by 2030.

Beyond policies already implemented for the agriculture sector, which makes up 48 percent of New Zealand's gross emissions, no new reductions are expected over the next four years. Agricultural reductions will come in the second (2026 to 2030) and third (2031 to 2035) budget periods, once the sector faces a price on emissions and as new technology becomes available.

Outside of specific sectors, the plan raised the idea of a new fund to encourage New Zealanders to adopt low-emissions behaviours.

"Promoting only small-scale, ad hoc changes risks a short-lived impact. We must drive deep and long-term systemic change to change behaviour at the scale required. The Government should take a central role in driving this," the plan found.

The Government also acknowledged advice from the Climate Change Commission about the differing roles for exotic and native forestry in reaching net zero emissions by 2050. An increasing carbon price under the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) "under current settings may drive more forestry rather than gross emissions reductions over the long term," the plan conceded.

In its final advice, the commission said exotic plantation forestry, such as Radiata pine, should be curtailed where possible. A long-term native forest carbon sink should instead be established to offset emissions from sectors that are difficult to decarbonise even in the coming decades, like aviation.

The plan promised only "to look at this issue more closely and if needed will change the way forestry is treated under the NZ ETS".

Any decision on changing the ETS rules would come by the end of 2022, the plan said. While the Government accepted the advice to establish a long-term carbon sink, it said this could involve both native and exotic species.

Acknowledging financial barriers to planting permanent natives, the Government said it would "deliver a broader package of changes to bring down the cost of planting native forests" by the end of 2023.

Consultation on the draft document ends on November 24. The Government expects to release the final Emissions Reduction Plan by the end of May 2022, in line with next year's Budget.