Today, Newsroom begins a special documentary and podcast series on the vital role water will play in New Zealand’s future.

Made by Wellington film-maker Magnolia Lowe, ‘Water—Rapuhia, kimihia: Quest for knowledge’ highlights the work of three leading researchers as they dedicate their lives to protecting different aspects of one of our most precious resources.

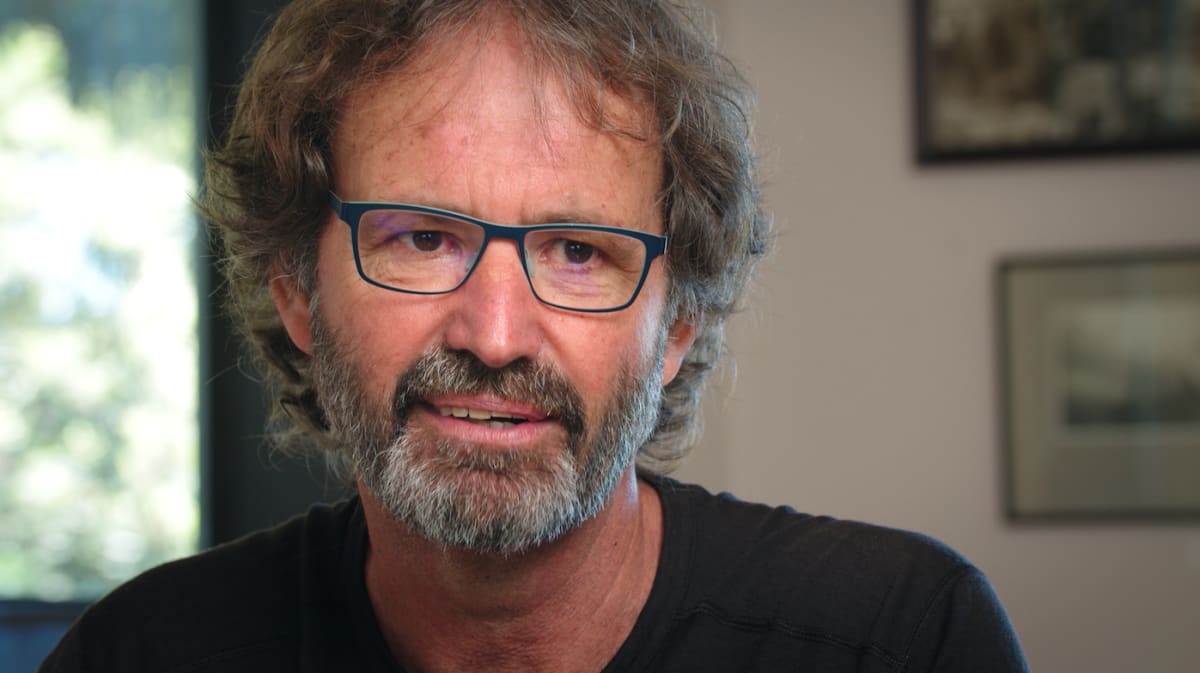

Part one profiles the work of ecologist Dr Mike Joy, a Senior Research Fellow in the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies in Wellington School of Business and Government at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.

Joy has been labelled ‘Doctor Doom’ for his pessimistic views on the state of our fresh water.

“It’s blatantly obvious, why don’t we admit that we’ve completely failed and start again?” says Joy.

In this article for Newsroom, Joy outlines why he thinks we need to urgently reduce the nitrogen levels in our water.

The Covid-19 pandemic has concentrated minds on short-term human health issues and long-term economic survival ones. But there are health issues lurking in the middle ground that we should be giving as much attention.

For all the attention focused on the state of freshwater in New Zealand over the past few years, relatively little has been said about the associated health threats – we have been too distracted by our inability to swim in our favourite rivers and by the declining state of freshwater ecosystems.

The majority of our drinking water in New Zealand comes from groundwater (53 percent), followed by rivers and lakes (26 percent), with the rest from rainwater. Contaminant levels are on the rise in groundwater, rivers and lakes, with nitrate levels in particular emerging as a huge red flag.

Recent research has highlighted the link between nitrates in drinking water and multiple negative health outcomes, in particular colorectal cancer. Evidence is also accumulating which links nitrates in drinking water with thyroid disease and neural tube defects. In particular, some recent large studies confirm long-term exposure to nitrate is linked to increased colon cancer risk. (The mechanism is thought to be from nitrate in water converting into the carcinogenic compound N-nitroso after ingestion.)

Colorectal cancer, encompassing both colon and rectal cancers, is the third most prevalent cancer and the second highest contributor to cancer deaths worldwide. Despite these high global numbers, New Zealand has some of the highest colorectal cancer rates in the world. Within the country, rates vary significantly, with the highest incidences in South Canterbury and Southland. By a staggering coincidence, these are also areas with high levels of nitrate in aquifers.

One critical issue for New Zealanders is that our current maximum acceptable value for nitrate in drinking water is not in any way related to colorectal cancer, thyroid disease or neural tube defects. Rather, it is based on the risk of “blue baby syndrome” (infantile methaemoglobinaemia, which reduces the ability of red blood cells to release oxygen to tissues).

A Danish study that calculated the exposure rate for 2.7 million people – the biggest sample size of any study to date – showed a significantly elevated risk of cancer with drinking water nitrate levels 10 times lower than our current maximum acceptable value.

As for the actual levels of nitrate in New Zealand drinking water at a national scale, I can’t yet give them, because no one organisation is collecting the data. Drinking water suppliers are not required to routinely monitor or report on nitrate levels below 50 percent of that dangerously high maximum acceptable value.

The reason nitrate levels in drinking water are going up is that to enhance plant growth we have been doing everything we can to get nitrogen out of the atmosphere and into the soil, where it can leach into groundwater and drain into rivers and lakes. In the past 100 years, globally we have doubled the inputs of reactive nitrogen going into our natural environment.

We have done this by using fossil gas to create synthetic nitrogen fertiliser, industrialising a job that used to be done for us by plants. Here in New Zealand, around a third of our polluting nitrogen fertiliser comes from Taranaki natural gas, with the other two thirds imported from the Middle East.

This conversion from natural to artificial food production has scaled up significantly in New Zealand over the past three decades. Over this period, the amount of nitrogen fertiliser we add to soils has increased by almost 250 percent, to a current amount of roughly 429 million kilograms a year. The nitrate lost to the environment from livestock systems has, of course, increased in tandem, to the point where around 199 million kilograms of nitrogen a year leaks into our waterways and aquifers.

We can measure this in our rivers and lakes, with an increased nitrate load 159 percent more than natural levels. This leakage from intensive farming shows up with 85 percent of waterways in pasture catchments (half of the national waterway length) now exceeding guideline nitrate limits. Over the past 30 years, 44 percent of monitored sites have nitrate levels increasing and nearly all of these sites have pasture catchments.

Groundwaters also are getting worse, with 35 percent of bores monitored nationally deteriorating, and it’s much worse in places like Canterbury, where almost all drinking water comes from groundwater and 48 percent of monitored bores have become more polluted with nitrogen.

There is obviously a need to look at the issue of nitrate in drinking water, and in fact this is under way. The Government has announced an inquiry with a task force to look into the problem in New Zealand.

Separately, a research group I am part of is investigating colorectal cancer risk and nitrate contamination in New Zealand drinking water, a collaboration between Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, the University of Otago, the University of Auckland and Loughborough University Scotland.

But any argument that we should wait for more research into the cancer implications of the nitrogen in our water is specious. It is patently obvious we urgently need to reduce nitrogen inputs into our water, not just for the sake of ecosystem health, but to reduce the butcher’s bill our people pay to cancer year in and year out.

There is growing pressure on farming to halt synthetic nitrogen use and evidence is accumulating that farmers can make more profit by reducing their use of artificial fertilisers.

Many New Zealanders have recently joined me in calling for radical new approaches to food production and our entire way of living post-Covid through the Better Futures Forum. This forum is determined to give government the mandate to make the tough decisions needed to give us a sustainable and resilient future.

There are viable and exciting regenerative solutions where we can produce food and fibre not dependent on fossil fuels. Based on ecological principles, regenerative farming systems mimic natural ecosystems, restoring rather than degrading the land and freshwaters over time.

It is worth noting also that in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic New Zealanders are likely to become more sensitive to a wide range of safety and health issues, and may well become more discerning as to the provenance of their food – as may consumers in our major export markets.

This is our opportunity to change to a more sustainable food production model in New Zealand.

Dr Mike Joy and his research are the subject of the first documentary film and podcast in Newsroom’s new series ‘Water—Rapuhia, kimihia: Quest for knowledge’.

Watch and listen to other episodes:

Episode 2: Sea Level Rise and accompanying podcast featuring Professor Tim Naish – available now.

Episode 3: Rights & Responsibilities and accompanying podcast featuring Professor Catherine Iorns – available now.

*Made with the help of NZ On Air*