One of the biggest questions at a Royal Commission’s hearings into the torture of children at Lake Alice was answered on the opening day. What came next was the bombshell.

The lingering question was: what role would Selwyn Leeks play?

Leeks was the man with the machine – the head psychiatrist at the notorious Lake Alice child and adolescent unit, near Palmerston North, who doled out electric shocks as punishment to children from an electro convulsive therapy (ECT) machine.

Torture, physical and sexual abuse was common at the unit, until it was closed in 1978. Hundreds of children were affected. However, the unit’s closure wasn’t the end of one of the darkest chapters of abuse in state care because Leeks – who has always denied wrongdoing – left for Australia.

Lake Alice has been more in the spotlight in recent years.

A claim by Lake Alice survivor Paul Zentveld prompted the United Nations Committee against Torture to, in December 2019, criticise successive governments for failing to properly investigate historic allegations of torture at the psychiatric hospital.

After the landmark decision, police re-opened their file on Leeks and said charges and extradition were possible. There are recent suggestions from within the police Leeks may face criminal charges.

Then there’s the Abuse in Care Royal Commission’s hearing itself. Set down for 12 days, it started yesterday, and the public very quickly became aware Leeks would be represented. A little over an hour into the morning session, commission chair Judge Coral Shaw called on Leeks’ lawyer, Hayden Rattray, to make submissions via video from Melbourne.

Rattray – a former solicitor for New Zealand’s Securities Commission, who has worked in Victoria, Australia, since 2010 – said dealing with serious allegations from nearly 50 years ago was a significant challenge, but the commission’s job was made harder by the statutory requirement for natural justice and fairness.

Leeks was assessed by a neuropsychologist in March, and her report was provided to the commission in April. “Dr Leeks is 92 years old,” Rattray said. “He has metastatic prostate cancer, ischemic heart disease, chronic kidney dysfunction.”

The neuropsychologist noted Leeks’ cognitive functioning “is most likely suggestive of Alzheimer’s disease, and that his functional decline is also supportive of a diagnosis of dementia”.

“As a core participant in this inquiry, Dr Leeks has the right to give evidence and to make submissions,” Rattray said. “But he is, by virtue of his age and cognitive capacity, manifestly incapable of doing either. Dr Leeks is neither aware of the matters before the inquiry nor cognitively capable of responding to them.”

Rattray represents a man “incapable of instructing me”, he said, adding that he’s incapable of understanding the inquiry process or meaningfully engaging with it.

Zentveld, surrounded by fellow survivors, was the first person to address the commission yesterday. He wasn’t rocked by the Leeks revelations.

Despite a report from a neuropsychologist, Zentveld tells Newsroom he won’t accept the “crock of shit” without factual evidence. “No one’s going to stand for that. We need proof that he’s like that.”

News of Leeks’ condition raises questions, Zentveld says, like if he’s so bad why is he living in his own house? It wasn’t clear from yesterday’s evidence where Leeks is living.

(Another question raised by Zentveld is, who’s paying Dr Leeks’ fees? Rattray says via email: “It wouldn’t be appropriate for me to comment on your query.”)

Zentveld says police are obligated to lay charges because “they have the UN to answer to”. “The police are on our side. They will do their job.”

(In 2010, the previous police investigation – heavily criticised by the UN Committee Against Torture – concluded there was insufficient evidence to charge Leeks.)

The Citizens Commission on Human Rights, a group aligned with the Church of Scientology, has for decades helped survivors’ drive for justice, including Zentveld’s case to the UN. New Zealand director Mike Ferriss, who attended yesterday’s hearing, says he doesn’t know what the Leeks revelations meant for the police investigation. “I hope they still lay the charges, and let him respond.”

Ferriss says Lake Alice isn’t just about Leeks. “Certainly it’s about what he did, and I think, given everything we know, he did commit those acts. The Royal Commission has also a duty to reveal why the state then covered up those acts as best they could.”

Leeks’ lawyer Rattray told commissioners yesterday he intended to view the hearing’s video stream and would contact the commission’s staff if he wanted to make submissions. (Earlier he’d said he can’t respond on Leeks’ behalf, or give evidence for him.)

Rattray told commissioners he was available if the required submissions from him. Zentveld says the final exchange left a gutted feeling in the packed hearing room.

The Royal Commission’s first witness was a stark reminder of the horror of Lake Alice and its ongoing effects.

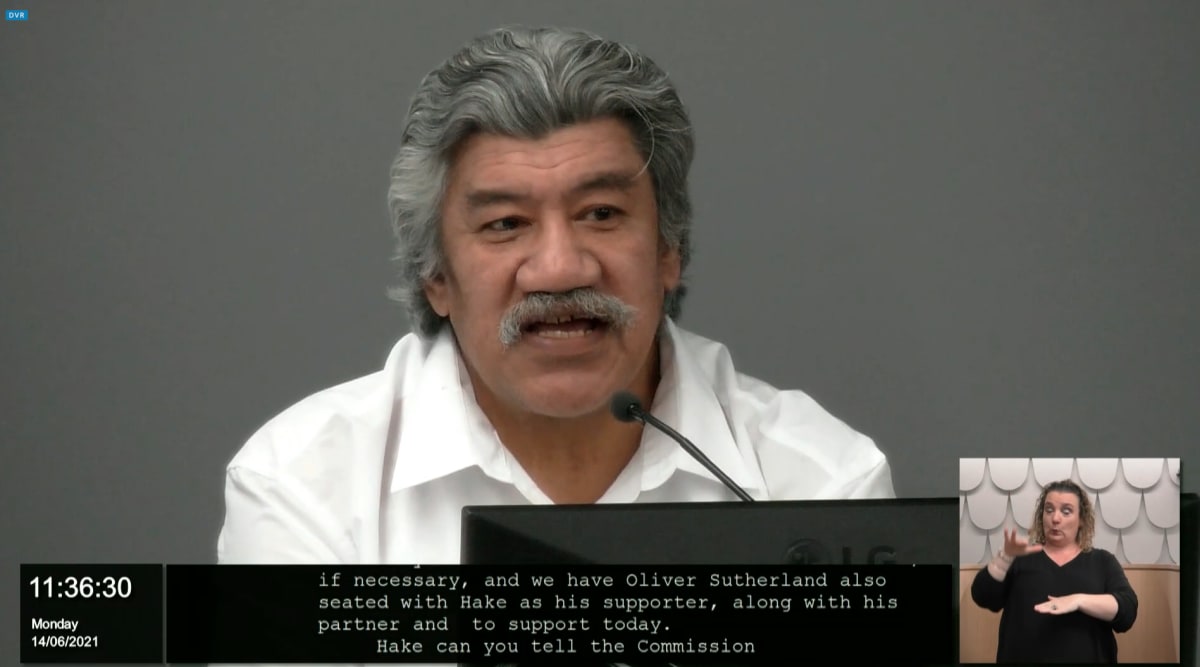

Hakeagapuletama Halo was sent to Lake Alice in 1975, age 13, and was subjected to electric shocks within a week. He still feels the effects of his 10 shock “treatments”, his written evidence says.

His childhood epilepsy came back, and he still has fits, which, his doctor says, means he can’t work. But the Ministry of Social Development wants him to switch from the invalids’ benefit to the working benefit.

Halo has “anger, fear, forgetfulness, hearing voices, stress, confusion and much more”. He has persistent nightmares and prefers not to sleep alone. “Once the fear comes, I cannot sleep.”

After being discharged from Lake Alice in 1976, Halo didn’t get any further schooling. “I think I would have had a normal life if it had not been to Lake Alice.”

Halo recalls meeting Leeks for the first time, a week after arriving at the child and adolescent unit. He’d been escorted upstairs and entered a room occupied by Leeks and three staff members. He didn’t know why he’d been called in. A small machine sat on a trolley beside the bed.

The 13-year-old was put on the bed and given a mouthguard. What looked like electric earphones, extending from the machine, with wet, white pads, were placed on his temples.

Is it going to hurt, Hake asked. Yes, it is, Leeks said. Please, I don’t want it, the youngster pleaded. “I am sorry, but it has to be done whether you like it or not,” Leeks replied.

The machine was activated and Hake was knocked out. The next time he wasn’t so lucky.

After that, the shocks were like “being hit by a sledge hammers on the head”, he said yesterday, exhaling deeply, his eyes downcast.

“Your body’s off the bed,” he said. “You’re straining to fling your arms but they’re holding you down.”

As the shocks continue, tears stream down his face and screams echo around the unit. Leeks and his staff are unrelenting. The machine is turned off and on again, multiple times. “It goes on until you’re knocked out,” Halo said. “That’s when it stops.”

“An exhaustive factual analysis reveals the events at Lake Alice to have constituted systemic and extensive child torture extending over a number of years.” – prime ministerial briefing in 2000

Beyond electric shocks, the children of Lake Alice – more than 400 of them between 1972 and 1978, taken there for bad behaviour and delinquency – also received painful injections of paraldehyde. There was sexual abuse, including from adult patients on the same hospital grounds. Days and weeks were spent in solitary confinement.

It was an atmosphere of terror, where children witnessed the fear and misery of others, and then awaited their turn. Some were not even 10 years old.

The buildings have been demolished, but that can’t erase one of New Zealand’s most shameful chapters. High Court Judge Sir Rodney Gallen described the physical and sexual abuse at Lake Alice as “outrageous in the extreme”.

Andrew Molloy, a lawyer assisting the commission, said yesterday: “The children were subjected to interventions, and threats of interventions, that posed as treatments but were administered without therapeutic intent and with the very opposite of therapeutic effect.”

Before this hearing, society hasn’t heard so many voices from Lake Alice all at once. And despite decades of complaints, and multiple inquiries, there’s still a yawning gap of accountability.

Yes, there was a carefully worded Government apology under Prime Minister Helen Clark, and payouts (less legal fees) to some survivors. But officials have pursued what has been described as “ongoing, prolonged, intentional delays, obstruction tactics and obstruction strategies”.

Frances Joychild QC, counsel for survivors, noted in the lead-up to a settlement of a class action by the Government in 2000, Clark was briefed by her executive personal assistant. He wrote: “An exhaustive factual analysis reveals the events at Lake Alice to have constituted systemic and extensive child torture extending over a number of years.”

The same briefing worried about the incalculable damage to the country’s reputation, should such a story take hold overseas.

“To this point in time, survivors have felt betrayed by the state and the police,” Joychild said yesterday. “This is a story that the nation must hear in all its horror.”

Leeks, meanwhile, still casts a long shadow over Lake Alice. The strength and definition of that shadow seems to depend on the light being shone by the latest police investigation. Given news of Leeks’ deteriorating health, survivors must be hoping the investigation wraps up quickly.