In the fourth part of Newsroom’s “Bad Things Happen” banking series, Nikki Mandow looks at merchant service fees and wonders is it time our banks – some of the most profitable in the world – gave retailers a break.

John* runs an independent bottle store. It’s an upmarket place, mostly wine, some spirits, beer fridge out the back. He’s been in the same ‘hood for 20 years, works hard, employs a few locals. Nice bloke.

In a good year, John’s salary – the profit he makes after the long hours running his shop – is around $50,000. He reckons many of his customers in his nice suburb would be shocked if they knew how little he takes home.

Some years he doesn’t make that much. One year he made $20,000.

It’s no secret profit margins in retail are low, and getting lower. John’s bottle shop turns over about $1 million a year. That makes his margin between 2 and 5 percent, depending on the year.

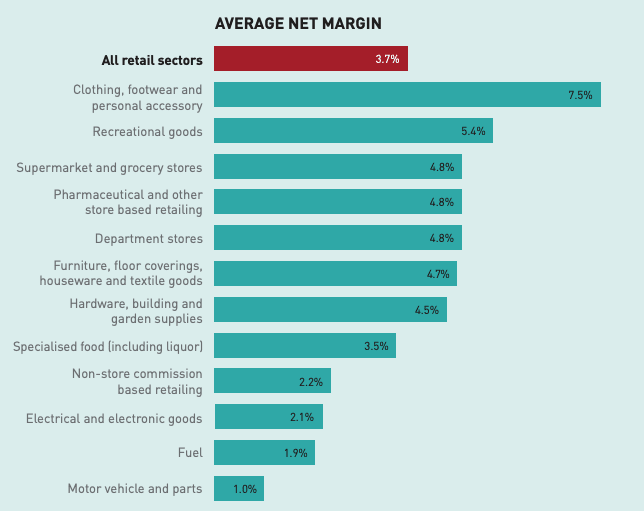

And that’s about par for the course. The average net retail margin, according to a 2018 survey by industry body Retail NZ is 3.7 percent. That will probably be less this year, what with the impact of the coronavirus.

Sometimes John wonders whether it’s worth it. But actually, he kinda likes his job, knows his customers, his wines. Business in the bottle shop is good post-Covid. John thinks that might be because no one travels, so no one can stock up on duty free any more.

No, what really pisses John off is not how little he makes; it’s how much he pays to the banks. Around $14,000 a year.

That’s almost 30 percent of what John earns.

And for what?

For moving money electronically from his customers’ bank accounts to his business account.

“I would understand if someone had to pick up a pencil and write on a balance sheet. But it’s done by a machine.”

It doesn’t make sense to him. He works long hours and earns $50,000. The banks spend seconds moving money from one account to another via an automated computer system and earn $14,000.

“It’s outrageous. What are they giving us? Almost nothing. I would understand if someone had to pick up a pencil and write on a balance sheet. But it’s done by a machine – there’s virtually no cost to them.

“I’ve gone berserk over the years trying to let people know the damage [the high fees retailers pay] does to a business. But nothing happens.”

This week something did happen. Under Covid-related pressure to push more retailers to allow contactless payments in their stores, Visa announced it was cutting the percentage “interchange” fee people like John have to pay the banks when their customers use a contactless or Paywave debit card.

The maximum interchange rate for Paywave debit transactions will fall from 0.3 percent to 0.2 percent of the total transaction from August 15. MasterCard will likely follow suit. And as interchange makes up a proportion of a retailers’ merchant service fees, they should fall too.

Visa is also cutting “contactless credit” rates, from present rates of between 0.85 and 1.57 percent, depending on the type of card, to between 0.65 and 1.37 percent.

However Visa’s standard credit card interchange rates for retailers remain the same. So small retailers will still end up paying between 1.25 to 1.97 percent of a transaction if their customer swipes or inserts their credit card. “Strategic merchants” (presumably the bigger, higher value ones) will pay between 0.5 and 0.98 percent.

Remember the interchange rate is just one part of the total merchant service fees.

Westpac Bank responded to the news, announcing it was cutting contact debit transaction fees to a maximum of 0.6 percent from September, and was lowering contactless credit rates.

ANZ is also cutting its rates, but less. Its contactless debit rate cap fell from 0.95 percent to 0.7 percent on August 1 for customers with ANZ bank accounts. For everyone else, the reduction was from 1.5 to 1.3 percent.

The bank, New Zealand’s biggest, says it is developing technology to allow it to cut contactless credit rates too, from October 1, but it didn’t say by how much.

Retail NZ chief executive Greg Harford welcomes the move to reduce contactless fees, saying it will help promote Paywave.

But he’s still worried, because not all fees have been reduced and because, according to his calculations, 30-40 percent of retailers are on what’s known as a “bundled” fee rate, meaning they may not benefit from the price reductions.

And although he says that “on a weighted average basis, a merchant should be paying no more than around 0.6 percent for in-store contactless debit and 1.4 percent for credit transactions” many, many merchants still are.

“It’s a huge issue. The cost of payments is the third biggest cost type for retailers.”

Newsroom got its pencil out and did some rough calculations based on numbers in the latest Retail New Zealand industry survey, published in 2018.

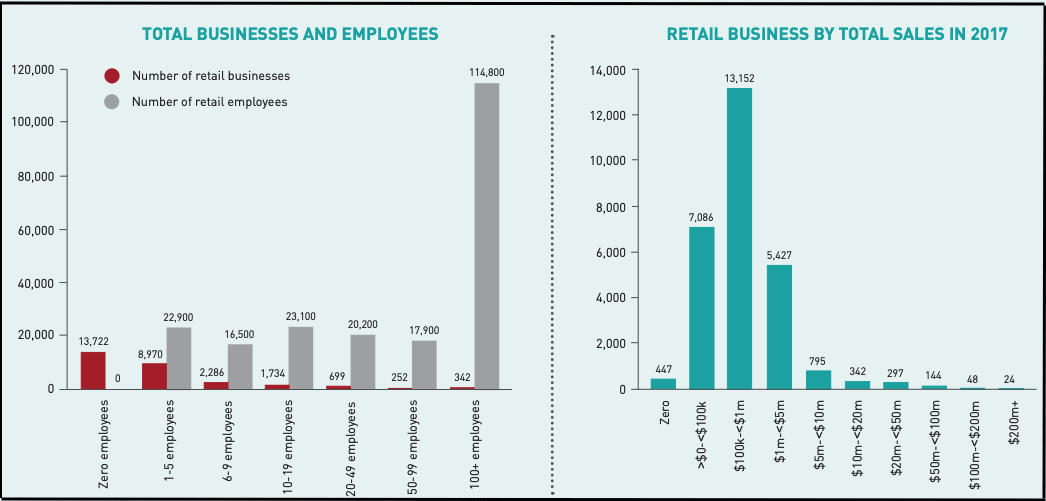

The research shows there were just over 35,000 retail outlets in New Zealand in 2017, of which almost three quarters (75 percent) are small or medium sized operations, turning over less than $5 million a year.

Total retail sales for the year were $92.3 billion.

That means the average store sold $2.6 million-worth of goods in 2017.

The average retail margin, according to Retail NZ, was 3.7 percent.

Which means the average retail store made $96,000. Big stores will likely have made more; small stores like John’s less.

But sticking with the average, Newsroom estimates the average merchant service fee – given debit fees are lower and credit ones are higher – is around 1 percent, with most of that going to the banks. If so, the fee adds up to $26,000 for the average store owner in New Zealand, largely for moving money electronically from one bank to another.

When the cardholder’s bank is the same as the store’s bank, the bank gets its share of the 1 percent of sales for moving money to itself.

Let’s say the banks get 80 percent of the merchant service fee (we don’t know the exact figure because no one releases it); that’s $21,000.

So to recap: the average NZ retailer works all year and earns, maybe, $96,000.

The banks expedite electronic payments at their store and earn, maybe $21,000.

That means banks earn $1 in fees for every $5 the retail owners get. For small stores, like John’s that’s likely more.

Bundled fees “should not be in the market”

But it gets worse. Retail NZ estimates something like 30 or 40 percent of retail outlets – likely smaller stores – are on that “bundled” fee rate. That’s a flat rate the retailer pays no matter what sort of card – credit or contactless – the customer uses.

Harford says for many small retailers that bundled rate is significantly higher than they would pay if they just paid transaction by transaction.

That’s partly because fees for contactless are considerably lower than those for credit cards, but the bundled fee has been traditionally set to reflect the credit card rate. The more debit transactions a shop processes, the more they lose out.

Moreover, the bundled rate is often historical, and doesn’t reflect the fact that under pressure from Government and the retail industry, merchant service fees have been gradually coming down.

Unless a merchant on a bundled fee “has some solid conversations with their bank”, Harford says, they often won’t be getting any advantage from fee reductions. Sometimes in the past banks have been proactive; more often they haven’t.

Many shop owners are paying merchant service fees of 1.7-1.9 percent, he says. It’s not unusual for a small store to be paying more than 2 percent. And Harford says he has come across instances of retailers paying 2.5-3 percent.

It’s hard to imagine any instance where bundled fees could be justified, Harford says, but they are still advertised by banks.

“These should not be in the market. We want to see everyone off a bundled rate and fees come down.”

Searching bank sites suggests bundled rates are often the first option on the banks’ list of suggestions for retailers.

Banks argue bundled rates are good for retailers because they give them certainty about what their payments will be.

That seems like a supermarket telling its customers an option of always paying $5 for 2 litres of milk is a bargain because they can balance their budget in advance. No matter that they could otherwise get milk on special for $3.50.

Examples on the Westpac site suggest the bundled options are suitable for a mobile coffee business and “a start-up”.

“I have a mobile coffee business, I need to take payments on the go. Westpac’s Get Paid solution has a fixed pricing plan which works well for me,” the recommendation says. “I can take payments anywhere. I have certainty of the merchant rate.”

Westpac customer experience hub general manager Karen Silk says its newly-announced fees will bring costs down, “particularly for smaller businesses where transaction volumes are lower and as a result costs have been traditionally higher.”

“For example, a café owner with relatively low volumes of transactions may have paid 10 to 15 cents in fees when processing a debit contactless payment for a $5 coffee. Now, they will only pay 3 cents.”

Retail NZ says reducing bank payment fees will boost retailer profits at a time they need it most.

“Retailers are facing very difficult times. It’s increasingly hard for them to make money.”

John agrees. Earning $55,000, rather than $50,000 would make a significant difference, he says. For many retailers facing tough times, paying less in merchant service fees could mean the difference between survival and failure.

Bank justification

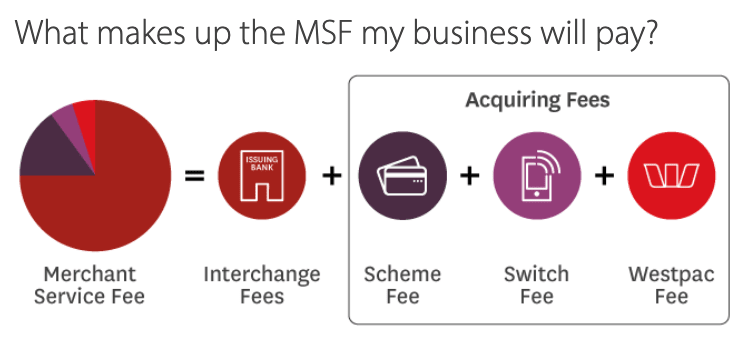

Banks argue the merchant service fee covers Visa and Mastercard costs, and the processing fee from the payment network or e-commerce gateway. But these are small compared with the fee that goes to the banks.

According to a Westpac document which provides a good overview of merchant service fees, they cover “card holder services, reward schemes, processing costs, merchant support, fraud prevention and authorisations”.

But banks aren’t saying how much any of those things actually cost them. Nor do they explain why they are charging the retailers for a rewards point system that benefits only the customer, not the retailer.

As John asks: “Why don’t the banks charge the customers the fee, instead of the merchants?”

And the answer is possibly because then customers would use their Eftpos, not their credit card. Meaning no fees for the banks.

More of that later.

Kiwi retailers pay more

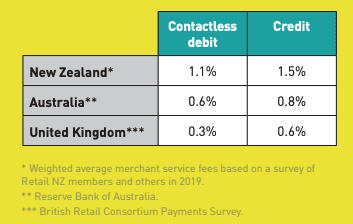

In the absence of any specifics about how the merchant service fee is calculated and how much it actually costs the bank to process card payments, the only thing you can really look at to judge whether the fees are fair or not, is how they relate to those charged overseas.

And here, New Zealand banks don’t come out well in terms of fairness. Their fees are way higher than those in comparative countries – particularly the UK and Australia.

The most recent comparisons were done in 2019 by Retail NZ.

If other banks follow Westpac’s lead and reduce contactless debit fees, that will bring New Zealand in line with Australia for those fees, but still leave our merchants paying double what they do in the UK.

However, as ANZ general manager Stefan Herrick points out, UK and Australian merchants have to pay for Eftpos and non-contactless debit.

“This transaction segment lowers the overall cost for merchants in New Zealand.”

Credit card fees here remain high compared with those overseas.

“The number of card machines in shops which have ‘no Paywave’ and ‘no credit card’ stickers on reflects the fact it costs so much for the merchant to accept those payments,” says one banking source.

Retail New Zealand’s Greg Harford says the complexity and opaqueness of the merchant fee system means it’s hard to get solid information on how much individual retailers are paying in service fees, but “we know some merchants are being overcharged.”

Since big retailers are able to negotiate significantly cheaper fees, the ones being overcharged are the small ones.

If a 1 or 2 percent fee doesn’t sound that much, remember the average profit margin in retail is 3.7 percent.

Why is it like this?

Historically, Eftpos payments are free for retailers, but over recent years banks have been keen to move customers away from Eftpos (where they receive no fees), to bank-branded Visa/Mastercard credit and debit cards.

The customer doesn’t lose out in the switch – but the retailer does.

Swipe/insert-your-debit-card-in-the-machine payments are also free from merchant service fees. But that means the recent move away from ordinary debit and Eftpos to online purchasing and contactless instore payments has been a bonanza for the banks – and a nightmare for stores.

Figures from ANZ, our biggest bank, show the ratio of Eftpos to contactless debit transactions before Covid was 20:80. Now it’s 30:70. Many merchants who resisted accepting Paywave before Covid, to avoid the high fees, felt they had to change their stance because of public health concerns.

A few have adopted surcharges to cover their contactless and credit card costs, but it’s not popular with customers and most shops don’t want to risk it.

Transparency and oversight

Harford says Retail NZ has been calling for greater transparency and regulator oversight of merchant fees for some years. But with Covid-19, reduction or regulation of fees has become urgent.

Many retailers have less money coming in, and with contactless becoming more prevalent, they risk earning less, but paying more fees to the banks.

While fee and cost structures are hidden by the banks, it’s hard to know what’s fair.

“Banks, global card payment networks, payments switches and other participants have invested very large amounts in creating, maintaining and enhancing a safe, secure and convenient payments system that provides significant benefits to all parties,” ANZ’s Stefan Herrick says.

A billion dollars for the banks

By contrast, New Zealand’s banks are some of the most profitable in the world. The major banks made more than $5.7 billion in profit in 2019.

It’s impossible to know how much of that profit is coming from retailer payment fees, and what the costs to the banks are of processing transactions. But one informed banking source, who didn’t want to be named, estimated New Zealand’s major retail banks likely took up to $1 billion in fees from merchants last year.

That would be $1 billion not going to retailers.

If you use the Retail NZ average numbers in Newsroom’s broad estimates above, you get three-quarters of the way to the billion mark. Multiply the average bank payment of $21,000 by 35,000 retail outlets and you get $735 million.

Harford says he’s never worked out the exact amount retailers are paying in merchant fees, but knows it is “hundreds of millions of dollars” a year.

And of course, that’s not counting money from bars, restaurants, cafes, and accommodation providers, also paying big bucks to banks for the luxury of processing money from their customers.

Harford says he’s never worked out the exact amount retailers are paying in merchant fees, but knows it is “hundreds of millions of dollars” a year.

By contrast, the combined assistance to retailers from ANZ waiving its contactless debit transaction fees between March and the end of July because of Covid was approximately $5 million, Herrick says. It was likely less for other banks because of their relative size.

(Then there’s the $10 a year that most banks charge their customers for their cards. As one customer wrote to Newsroom: “I am charged $5 every six months for the ‘privilege’ of having a Visa-debit card so I can use paywave to access my own savings. I’ve recently returned from the UK where paywave cards are standard and automatically provided at zero cost.”

Newsroom’s banking source said charging $10 a year for these cards was “hard to justify as the majority of the work is automated behind the scenes”. But that’s another story – Bad Things Happen: Fees Fees Fees.)

“We aren’t expecting merchant service fees to be zero. We just want them to be fair.”

Rebecca Fairbrother worked in retail payments at the Reserve Bank of Australia, before coming back to New Zealand and setting up Magnet (the Merchant Advocacy and Guidance Network) an industry body helping retailers reduce their costs for accepting cards.

She says her organisation isn’t expecting merchant service fees to be zero. It just wants them to be fair.

She says there’s no reason why New Zealand retailers pay higher fees on contactless and credit cards than their counterparts in Australia and the UK. Except that in both those countries, interchange fees are regulated by the government, Fairbrother says.

And that makes a big difference.

Trying to fathom merchant service fees

Merchant service fees are complicated and almost completely secret. But it’s clear banks receive by far the biggest portion. Westpac’s website has the clearest visual representation of how the merchant service fee is made up (see graphic below). The slices of the pie are not to scale, but it gives an idea of how the fee works, and it would be pretty similar at the other big banks.

Scheme Fee: Charged by Visa, Mastercard or Union Pay for provision of the card payment services.

Switch Fee: Charged by the payment network or e-commerce gateway (eg Paymark, Verifone or Payment Express) to process the transaction.

Westpac Fee: Charged by the retailer’s bank (in this case, Westpac). The fee covers “merchant support, fraud prevention and authorisations”.

Interchange fees are the biggest portion of the fee, and are particularly unfair, Fairbrother says, because banks use a lot of the money they get to fund their card reward schemes.

This means retailers are paying fees which fund reward schemes that benefit customers, but not retailers.

Even worse, the reward schemes incentivise customers to use credit cards, not Eftpos. The more customers that switch, the higher the merchant service fees.

Because it’s not the customers paying the fees, there’s no incentive for them to use a cheaper rather than a more expensive card payment – unless there’s a surcharge.

It’s a double negative whammy for retailers. Particularly the smaller retailers.

Smaller retailers pay higher fees

A 2016 Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment report into issues with the retail payment system hinted at a connection between generous credit card reward programmes and high interchange and therefore merchant fees.

“While the impacts of interchange regulation need to be more formally assessed, broadly, it would serve to reduce the MSFs paid by merchants, and would likely reduce the generosity of rewards programmes offered by issuer,” the report said.

Again, it’s the smaller retailers that lose out, Fairbrother says.

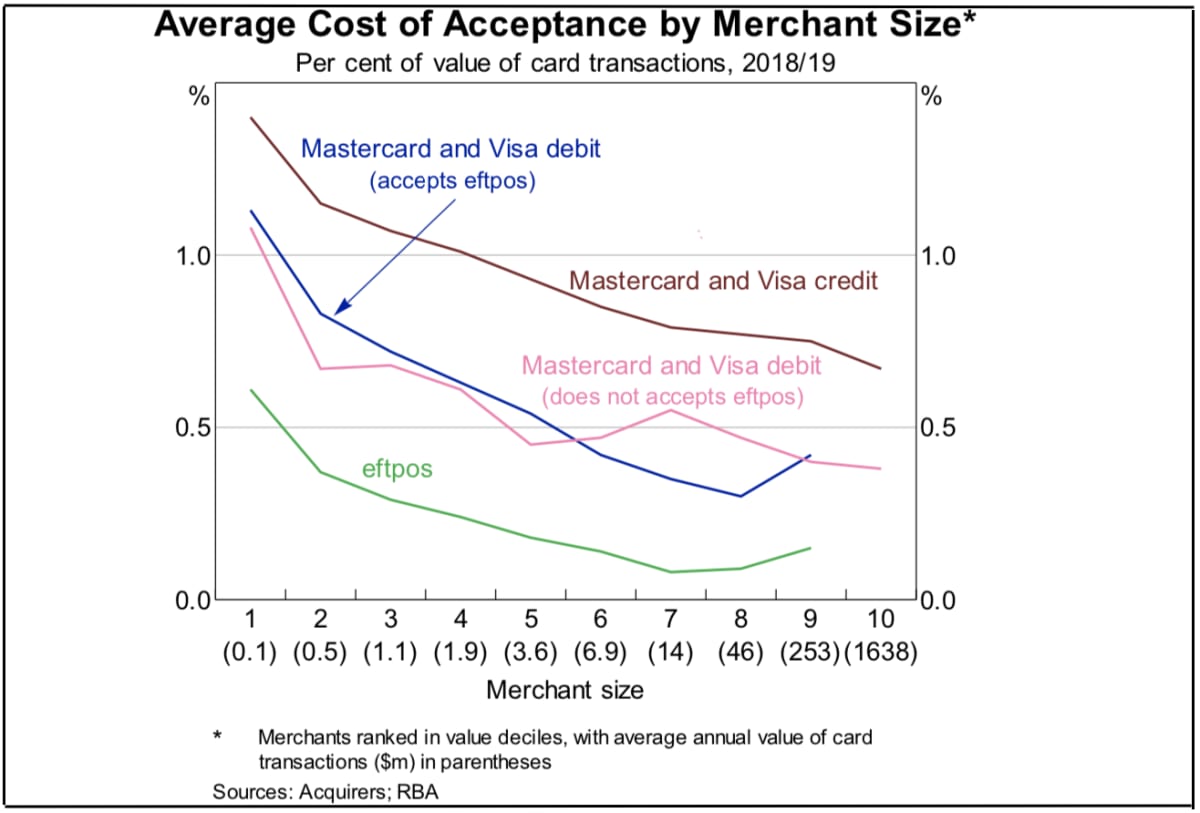

“MBIE found smaller businesses were paying higher fees than larger businesses – in some cases more than double,” she says.

Nothing much has changed since. For Visa credit card payments, for example, just the interchange part of the fee can vary from 0.5 percent for “rate 1” retailers to 0.98 percent for “rate 6”. In between, rate 2-5 retailers pay between 0.55 and 0.8 percent.

Which retailers fit into which category is a mystery, as is how total merchant service fee numbers are calculated for particular retailers.

But in the more regulated Australian market, where the Reserve Bank releases data on merchant fees, the numbers show how they are significantly higher for smaller retailers.

Bad things happen when no one regulates the banks

Fairbrother says relying on banks to do the right thing hasn’t worked in the past. She wants to see Consumer Affairs Minister Kris Faafoi regulate retail payments.

Faafoi threatened interchange regulation back in 2018, but since then the issue seems to have slipped off the Government’s radar, Fairbrother says.

Back in 2017, Retail NZ called for standards body Payment NZ to take a much more proactive role in terms of oversight and transparency around merchant service fees, both in terms of a breakdown of the fees charged to retailers and the costs for banks of processing payments.

“Every quarter that goes by and he doesn’t regulate, the banks make millions.”

“The Minister [Kris Faafoi] needs to say ‘We’ve had five years of the amount banks collect in fees increasing regularly, and now we’re going to regulate’,” one industry source told Newsroom.

“He’s threatened it since he came in – but he’s said he wants to talk to the schemes, wants to engage, discuss it further. It’s a delaying tactic.

“Every quarter that goes by and he doesn’t regulate, the banks make millions.”

Faafoi told Newsroom that “while regulation on card fees is an option, a sector-based solution is preferable”.

*John did not want his real name used

Newsroom’s Bad Thing Happen series is focusing on banks’ treatment of customers. The series takes its name from a quote from Financial Markets Authority chief Rob Everett that “bad things happen” when there’s no regulation of banks.

Get in touch with Newsroom – nikki.mandow@newsroom.co.nz

Part 1 – The tax on first-homebuyers

Part 2 – Giving our money to the banks for nix

Part 3 – Fees fees fees